- Home

- Sarah Outen

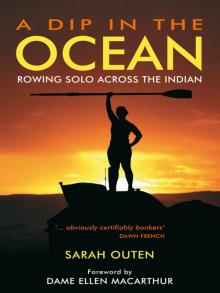

A Dip in the Ocean

A Dip in the Ocean Read online

A DIP IN THE OCEAN

Rowing Solo Across The Indian

Sarah Outen

A DIP IN THE OCEAN

Copyright © Sarah Outen, 2011

Map by Robert Littleford

Plate section credits: Sam Coghlan, René Soobaroyen, Helen Outen, Ricardo Diniz and Sarah Outen

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced by any means, nor transmitted, nor translated into a machine language, without the written permission of the publishers.

The right of Sarah Outen to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Condition of Sale

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent publisher.

Summersdale Publishers Ltd

46 West Street

Chichester

West Sussex

PO19 1RP

UK

www.summersdale.com

eISBN: 978-1-84839-449-0

Substantial discounts on bulk quantities of Summersdale books are available to corporations, professional associations and other organisations. For details contact Summersdale Publishers by telephone: +44 (0) 1243 771107, fax: +44 (0) 1243 786300 or email: [email protected].

For Dad, thank you for showing me how to live

For Mum, thank you for helping me chase the dreams

For Taid, I wish I could have written this faster

Thank you for seeing me home

‘It is not the goal but the way there that matters and the harder the way, the more worthwhile the journey’

Sir Wilfred Thesiger

I’ve received a splendid email

From a most courageous female.

Battling onward to Mauritius,

Lone among the flying fishes,

Albatrosses, giant whales,

Turning turtle in the gales.

To hell with Health and Safety rules,

She’s in tune with tuna schools.

She’ll dance, while others dance in bars,

With pilot fish and Pilot Stars.

I have not the faintest notion

How to brave the Indian Ocean

In anything that keeps afloat,

Let alone a rowing boat.

But Sarah takes it in her stride,

And going with her, for the ride,

A book, or audio CD

Read by Lalla and by me.

To speed her trip to its conclusion

We’re reading her The God Delusion!

So fly the flags, with sirens hootin’,

And raise a glass to Sarah Outen.

Richard Dawkins

Foreword by Dame Ellen MacArthur

When I first met Sarah at the London Boat Show she was full of energy, humour and adventure and I warmed to her instantly. Reading this book you will warm to her too. She is honest, open, courageous and inspiring, and taking you on her journey with her she’ll have you holding your breath one minute, and then laughing out loud the next. Understanding the oceans I can just begin to comprehend what she’s been through at sea, but her story on land is equally compelling. She has written this book wonderfully and has a contagious love for life which jumps right out of the pages at you! Sarah – I can’t wait for your next book!

Ellen

Prologue

The Seed is Sown

‘Whatever you think you can do, or believe you can, begin it. Boldness has genius, power and magic in it’

Goethe

It all started while I was at Oxford. Room 24, Main Building, St Hugh’s College, December 2005. I was sitting at my desk chewing a pen, surrounded by open textbooks and piles of notes. I was trying, quite unsuccessfully, to write a proposal to study basking sharks in Scotland that summer. My degree was biology, so that wasn’t unusual and neither was my procrastination; it was a rowing day after all and I was hungry for some action after too many hours indoors. I typed distractedly at my laptop, clock-watching and already thinking about my pre-training snack: a banana, a malt loaf, a Mars bar or all three? For the umpteenth time that day I opened up my inbox and read through the already-read emails, taking as much time as I possibly could. While I was reading a new one arrived with a ping. Result; at least another two minutes of beautiful time-wasting lay ahead.

I paused. And then I smiled as I read the subject line: ‘Ocean Rowing Races’. This was going to be more than two minutes’ grace from the proposal; it was easily the most exciting email I had ever received. I clicked and read an advert for a rowing race across the Atlantic. I had only ever rowed on the Isis and, whilst I had sailed a bit, I had never crossed an ocean. An ocean! Across a whole ocean in a rowing boat? I was speechless. I put my feet up on my desk and leant back on my chair, rocking on the two back legs in exactly the way you’re always told not to as a child, thinking and spinning the pen in my fingers. I was hooked by the idea of it; oceans and rowing were two of my favourite words and I was sure that if I put the two together they would make an incredible adventure. I had always wanted to see what it was like to make a big journey in the wild under my own steam, living and breathing the raw power of the elements, at one with nature. With no specific plans for life after graduation in a year’s time, I decided there and then that I would start with an ocean row. I wasn’t sure which ocean, or when, or how, or who with, and I don’t know why I was so sure of myself but I knew that I would do it.

In 2009 I did it, rowing solo across the Indian Ocean from Australia to Mauritius. It was a journey of more than just an ocean and it was far more than a rowing trip. It made me and it has shown me all the more clearly that life is for living, here and now, not tomorrow or some other day – because you never know what might be over the next wave or round the next corner. You have to make the most of the moment, or the adventures and opportunities might fade with the sunset and you will be forever left wondering what was over the horizon.

This is my story and I hope you enjoy it.

Sarah Outen

November 2010

Chapter 1

Portrait of the Rower as a Youngster

‘Life is either a great adventure or nothing’

Helen Keller

I couldn’t see any clear water – it was all white behind me and more waves were breaking. I felt a cold numbing fear that I was about to be obliterated. I had just enough time to shove the phone in the cabin and lock the door before throwing myself to the deck, holding on tight to the safety rails.

As I screamed, a bomb of a wave exploded over the boat and my world went white. But it was dark somehow, beneath the water, it was loud and I could taste salt everywhere. I was a rag doll, somersaulting through the surf which was now rushing us along the reef, growing louder and louder. And then I breathed a sweet breath – we must have come back around. I had floated off Dippers on my line and was surrounded by fizzing water while the wave receded. I looked round and saw no one and nothing but surf. I screamed again, and even I struggled to hear it over the sound of crashing waves. Dippers tilted over to one side with the water on deck but I scrambled on board, heaving myself through the safety rails. An oar was broken and the throw line was tangled, but there was no time to do anything but hold on; another wave was on its way. I knew that the reef must only be metres below now and with it certain annihilation.

I remember my dad once compared me to a carthorse. I like to think that this was his way of saying that he thought I was resilient and had stamina and

strength, hopefully both in mind and body. I had to be, really; I was the only girl sandwiched between my two brothers, Michael and Matthew, and our family was always on the move, professional nomads of the Royal Air Force. Dad was an officer and so change became the norm for us from very early on as we trooped all over. By my seventh birthday I had already chalked up three infant schools and lived in five different houses in three different countries. Nothing too exotic, mind; Wales is as foreign as I remember, though we lived in Europe for my first couple of years.

The lack of interesting postings was due to Dad’s ill health. In my memory he always had arthritis; it was diagnosed when I was toddling about and he was just inside thirty. Unfortunately it was one of the worst forms of all – rheumatoid arthritis. This causes the immune system to go haywire, attacking itself and wreaking havoc on every joint in the body, causing inflammation, disintegration and degeneration. One of my memories is of him sitting down at the breakfast table with a mountain of tablets beside him, wearing splints on his wrists, and sometimes spending days at a time in bed, too sore to move. Too sore even for a hug. Too sore to do anything but sleep and hope and fight on for a better day. If I was a carthorse, then Dad was a superhero carthorse. When you are fighting pain twenty-four hours a day with a crumbling skeleton, stamina takes on a whole new meaning. In my mind at least, he was as strong as an ox.

Another defining period in my own evolution as a carthorse (remember, we’re thinking resilience and stamina here) is my time at boarding school. When I was seven, one of my RAF friends boasted that he would be going off to boarding school the next year. I was rather in awe of the idea, and thought he must be very grown-up and that I must be missing out on some sort of grand adventure. I started a campaign of pestering to go, too, and the next school year I started at Stamford Junior School in Lincolnshire, sporting a regulation crimson corduroy beret and looking perfectly ridiculous. My older brother Michael joined the boys’ version on the other side of town, with no ridiculous headwear in sight, much to my annoyance. Now, some might recoil at the thought of my cruel parents packing us off to boarding school at the sweet young age of eight and ten, but it made sense. It promised stability in our so far very unstable education; we could also make friends and keep them, settle in, and progress through school uninterrupted for the first time in our lives. My own reason for wanting to go was not at all sensible and based purely on the idea of it being a permanent sleepover, and therefore a lot of fun.

It didn’t start out quite like that, and I roundly hated my first half term, writing long tear-smudged letters home to my parents warning of my bid to get myself expelled. Truth is, I had no idea about how to get myself expelled, and I don’t think I had the balls to do it anyway. It was tough for my parents as well; later on, Mum said that she cried all the way home after every time she dropped us back at school at the start of term. I now see that it was a huge thing for them to do and I am grateful for it and all those useful things it taught me – independence, tolerance and friendship. Once I settled down I loved it. My favourite thing was the school grounds and the hours we spent outside playing and doing all the things inquisitive, active children love to do. Even at eight I was an adrenaline junkie, keen to test my boundaries and see how fast I could go. One day I did just that by rolling down our favourite grassy hill in a plastic barrel, emerging rather bruised and dazed at the bottom.

Thankfully, the holidays were made of real adventures; Dad knew all about these and Mum knew how to make a fine lunch, so our family was well set up for some happy times, as long as Dad wasn’t too sore. At home we often pitched tents in the garden and camped out overnight, complete with hot water bottles in winter; in the summer we caravanned all over the UK and later on we had a share in a canal barge. My brothers were keen fishermen and I was quite content exploring and painting and whittling and reading, so we were easily entertained by rural campsites beneath mountains, by beaches or next to babbling rivers. As anyone who has camped in Britain knows, it was nothing flash or fancy, just freedom and encouragement to have a go at new things and enjoy our surroundings.

The Family Walk was a great tradition and we clocked some good mileage in the years before Dad’s arthritis stopped them. I was nine when he first taught me about using a map and compass, which was a big step for me and very exciting. It was on a mountain walk that he and I left the rest of the family walking down the normal path, while we returned cross-country. Dad went in front with his floppy hat, big red backpack and the map around his neck and I trotted along behind, following his huge steps, and alternately singing and asking a barrage of questions as children do. We trekked through bracken, down scree slopes and skirted round bogs, Dad hauling me out when I sunk in one of the latter up to my knees.

A year later we camped under Cadair Idris, a craggy Welsh mountain, and one day went on a walk to the summit. I had actually planned what I would wear for a whole week before, such was the anticipation. As the path wound out of the campsite through the shade of the damp forest I imagined the top. Would there be a cairn? Would we see the sea? We three children played in the icy streams and scrambled on rocks the whole way up and opted for an afternoon playing in the glacier lake before the final peak rather than punching on for the summit. Dad and I went up again a few days later and this time I carried my own rucksack, full of all sorts of useless things that I was sure we couldn’t do without and that of course we didn’t actually use at all. The beach mat, for example – nice idea but not at all necessary. It rained all day, turning paths into streams and our boots into puddles. Mist crept over the summit ridge, alternately hiding and revealing the views as we neared the top. I was hooked – it was so mysterious and beautiful – and I found myself falling in love with the wild. After eating a stack of soggy sandwiches, while sheltering behind a rock in the whiteout, we headed back down without reaching the top. With this, I was already learning to respect the elements; formative lessons to stay with me forever. To get to the top of that mountain is still on my list of things to do, sixteen years later.

As I grew up I had more adventures and dreamed of others; I didn’t know what or how or when, but I knew deep down that I wanted to make a big journey one day. I wanted to feel what I had read other people write about: excitement, fear, the unknown, the struggle, exhaustion and survival. I loved challenges, especially those where I truly didn’t know if I could make it, and the satisfaction of being exhausted after a long walk or bike ride. Fear was exciting and I chased those moments where I was pushed outside my comfort zone, eager to test and show my strength. I climbed trees until branches snapped; I ran races as hard as I could until I thought I was going to faint. In my head, I was George from Enid Blyton’s Famous Five, strong, adventurous and as stubborn as can be.

I was competitive, too, and I don’t think that was entirely due to having two brothers, but more about pushing myself and testing my strength. I found it so raw, so defining to have such a narrow line between success and failure when I stepped up to the discus cage, for example, the only person in the world capable of controlling the outcome. Win or lose, it all rested on my shoulders. The more I studied and played, the more I found that perfection was untenable and always would be, which was (and still is) simultaneously motivating and frustrating. On and off the sports field, I was very driven and very busy, actively filling my time with everything I loved, mainly sport but other stuff too. People ask me what drives me, and I think part of it comes from having watched Dad suffer so horribly. It didn’t take me long to work out that life is too short to wait and health too precious to waste.

I was eleven when Dad was medically discharged from the RAF in 1996. He limped more and more as his feet deteriorated, until his walk became a shuffle and his ankles were so deformed that they didn’t look like ankles at all. They were swollen beyond all recognition, his toes deformed and then latterly fused solid with operations, in an attempt to stop them curling into knots. A wheelchair appeared from time to time, a walking stick at others, and

then the wheelchair became the norm. Seeing my huggable giant of a dad, being beaten down like this was so sad – he had always seemed so big and strong to me, even with the arthritis. Unfortunately, his health was only ever going to get worse. The pain wasn’t just physical, and with the added side effects of the drugs, he had an unthinkably rough time of it. We all did, but for him it was hideous. The drugs affected his mood, he gained weight, looked sick, felt sick and emotionally struggled with the pain and the consequences of it – the immobility, the loss of independence and freedom. In many ways I think he grew old before his time. I can’t imagine how hard it must have been for Mum too, often doing the work of two parents, while also nursing him when he was at his worst. My parents’ marriage is a beautiful example of unconditional, devoted and selfless love and I salute them both for showing me how to carry on through the best of times and the worst of times.

Chapter 2

In the Beginning Was the Water

‘There is nothing more enticing, disenchanting, and enslaving than the life at sea’

Joseph Conrad

After Dad left the RAF we moved to Rutland so that Michael and I could carry on at Stamford as day pupils through our senior years. It is a tiny English county, nestled in the Midlands, little known and landlocked. Lots of people find it quite surprising, therefore, that I am so in love with the sea. It all started when I followed Michael to our local canoe club when I was about twelve, partly because I wanted to have a go and partly because of the need, if only in my head, to be as good as him. Sibling rivalry prevented me from admitting it at the time, but I looked up to him and still do – we are chalk and cheese in many ways, as different as black from white, but for the values and traits that we’ve inherited from the same gene pool. As teenagers we wound each other up so fiercely that I’m surprised Mum and Dad didn’t put us up for sale but I’m happy that I followed him to the water all those years ago. I was soon hooked and found that I loved the longer journeys, especially on the coast.

A Dip in the Ocean

A Dip in the Ocean